“That’s not what I meant – you’re taking it the wrong way.”

Whether you’ve said these words or heard them during a difficult conversation, you’ve experienced deflecting firsthand.

We all use this psychological defence mechanism sometimes, redirecting uncomfortable emotions or feedback away from ourselves when things feel too overwhelming. Whilst deflecting might protect us from immediate discomfort, it creates deeper problems in our relationships and prevents genuine self-growth.

This article explores what deflecting really means, why our minds resort to it, and how we can learn healthier ways to handle life’s uncomfortable moments.

What Is Deflecting in Psychology?

Deflecting is a psychological defence mechanism where someone avoids addressing uncomfortable emotions, feedback, or responsibility by redirecting focus through blame-shifting, subject-changing, or humour. It protects short-term comfort but prevents genuine self-reflection and damages relationships over time.

If you think you might be guilty of deflection, think of deflecting as your psychological immune system overreacting. Just as your body might develop allergies by being overly protective, your mind can develop deflecting patterns that once kept you safe but now hold you back.

Defence mechanisms like deflecting aren’t inherently bad; they’re survival strategies our minds create to manage psychological threats. When someone gives us feedback that challenges our self-image, or when we face emotions that feel too big to handle, our brain’s threat detection system kicks in. The result? We redirect, minimise, or avoid – anything to escape that uncomfortable feeling.

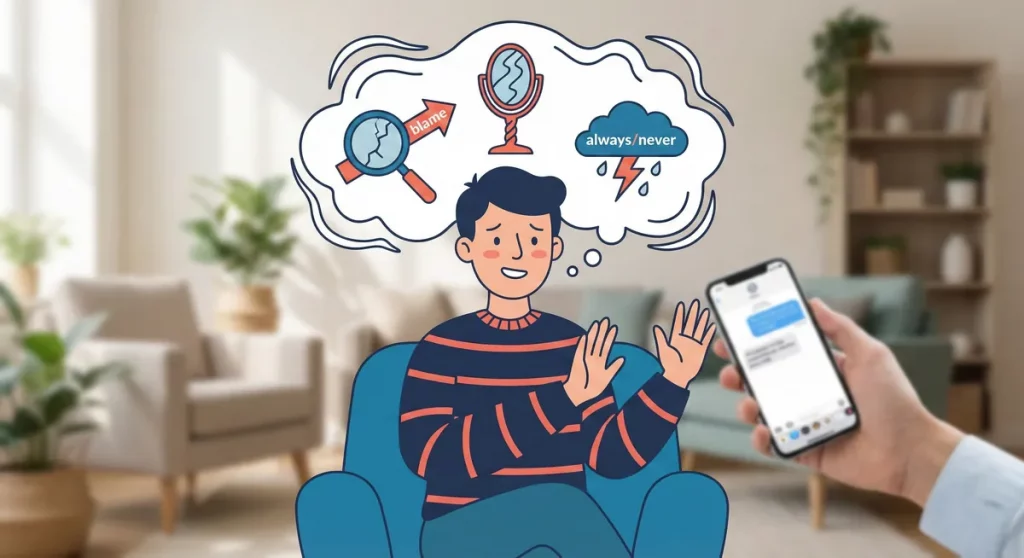

In CBT terms, deflecting often stems from cognitive distortions like “all-or-nothing thinking” (if I’m wrong about this, I’m a complete failure) or “mind-reading” (they think I’m incompetent). 1 Understanding these patterns is the first step towards change.

Deflecting vs. Setting Healthy Boundaries

One common confusion we encounter is the difference between deflecting and setting legitimate boundaries. This distinction matters because many people worry that protecting their emotional wellbeing means they’re deflecting, whilst others use “boundaries” language to justify avoiding accountability. Here’s how to tell them apart:

| Scenario | Deflecting Response | Boundary-Setting Response | Key Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving constructive criticism at work | “Well, you made mistakes in your presentation too” | “I appreciate the feedback. I need some time to process this before we discuss further” | Deflecting attacks back; boundaries request space respectfully |

| Partner raises relationship concern | “You’re being oversensitive, it’s not that serious” | “This feels important. Can we discuss it when we’re both calm this evening?” | Deflecting minimises; boundaries acknowledge whilst managing timing |

| Friend asks about difficult topic | “Why are you always prying into my business?” | “I’m not ready to talk about that yet, but I appreciate you caring” | Deflecting accuses; boundaries communicate limits kindly |

| Admitting a mistake | “It’s not my fault – if the instructions were clearer…” | “I made an error. Let me fix it and learn from this” | Deflecting shifts blame; boundaries include accountability |

Notice the pattern: boundaries maintain responsibility whilst requesting reasonable limits, whereas deflecting redirects focus away from the issue entirely. When you set a genuine boundary, you’re protecting your capacity to engage meaningfully; when you deflect, you’re refusing to engage at all.

What Is Deflecting? Understanding the Defence Mechanism

Deflecting shows up in countless ways in our daily lives, from subtle conversation shifts to elaborate justifications. It’s a learnt behaviour that often begins early in life, particularly in environments where showing vulnerability felt unsafe or led to criticism.

How Deflecting Manifests in Daily Life

Someone changes the subject whenever their partner tries to discuss relationship challenges, suddenly remembering urgent emails or becoming intensely interested in what’s for dinner. These everyday deflections might seem harmless, but they accumulate into significant barriers to intimacy and growth.

The Difference Between Deflecting and Other Defence Mechanisms

Whilst deflecting redirects attention outward, other defence mechanisms work differently. Projection involves attributing your own feelings to others (“You’re the one who’s angry, not me”), whilst denial refuses to acknowledge reality exists at all. 2 Deflecting acknowledges the issue exists but refuses personal engagement with it – a crucial distinction for understanding your own patterns.

Why Do People Deflect? The Psychology Behind the Behaviour

Understanding where deflecting came from doesn’t excuse the behaviour or its impact on others. It means you can face the pattern without shame.

The Neuroscience of Deflecting

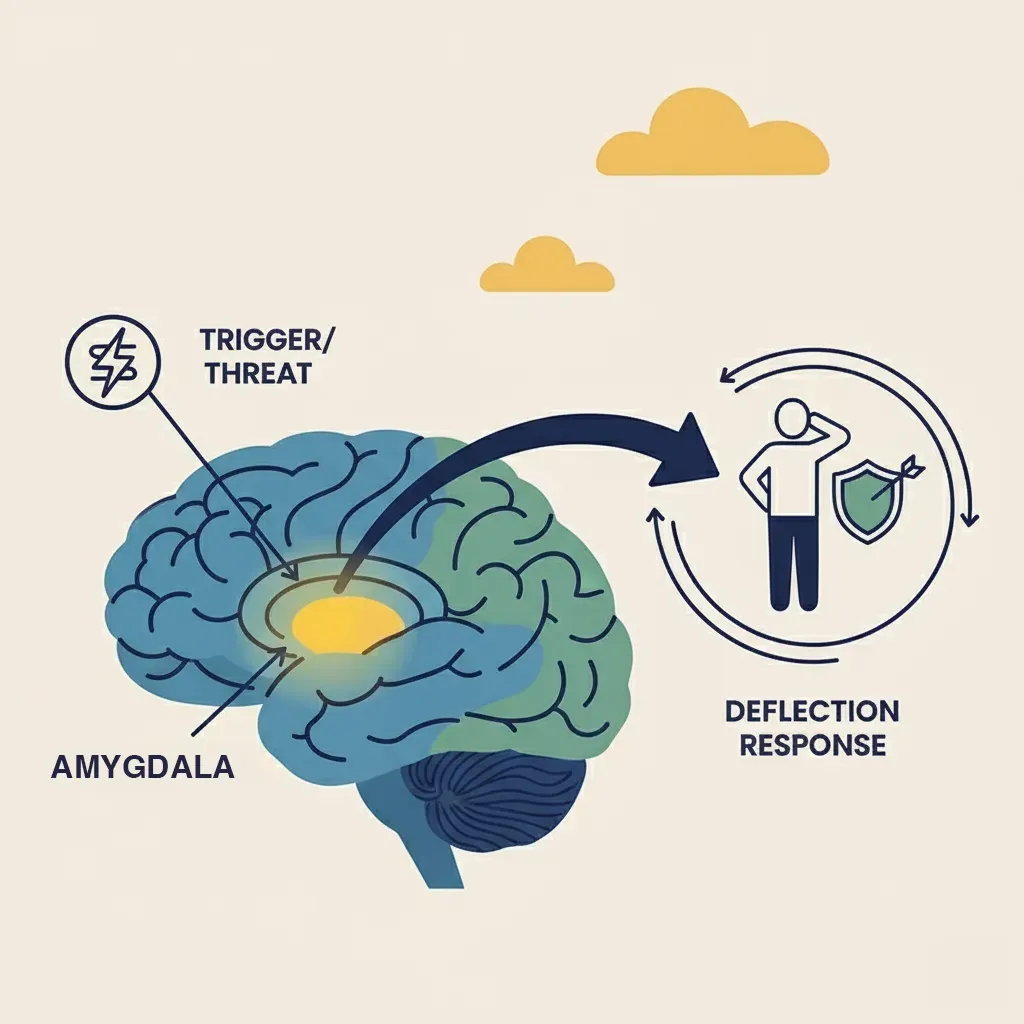

When faced with perceived criticism or emotional discomfort, your amygdala (the brain’s alarm system) activates before your prefrontal cortex (responsible for rational thought) can assess the situation. This fight-or-flight response happens in milliseconds, triggering deflection as a form of psychological flight. 3

Research shows that people with histories of criticism, particularly in childhood, develop more sensitive threat detection systems. 4 Your brain literally learns to see feedback as danger, responding with deflection before you consciously choose to. This isn’t character failure – it’s your threat-detection system working overtime. Recognising this biological pattern helps you approach change with curiosity instead of self-criticism.

Common Cognitive Distortions That Fuel Deflecting

In CBT, we identify several thinking patterns that make deflecting more likely:

- Catastrophising: “If I admit this mistake, everyone will think I’m incompetent forever”

- Mind-reading: “They’re bringing this up to make me look bad”

- Black-and-white thinking: “If I’m not perfect, I’m worthless”

- Personalisation: “Everything that goes wrong must be someone’s fault”

These distortions create an internal environment where deflecting feels like the only safe option. Recognising them helps you develop alternative responses.

Childhood Roots and Trauma Connections

Many of us learnt to deflect in childhood as protection against overwhelming criticism, unpredictable caregivers, or environments where taking responsibility led to harsh punishment rather than supportive problem-solving. If admitting mistakes meant shame rather than learning opportunities, deflecting became a survival skill.

Common Signs You’re Deflecting (or Someone Is Deflecting to You)

Recognising deflection is challenging because it often feels justified in the moment. Below, you’ll see the behaviours that usually point to deflection.

Identifying Your Own Deflecting Patterns

You might be deflecting if you:

- Feel immediately defensive when receiving feedback

- Find yourself saying “Yes, but…” frequently

- Change subjects when conversations become emotional

- Use humour to avoid serious discussions

- Feel physically tense or notice your heart racing during difficult conversations

- Have a mental list of others’ faults ready when criticised

- Struggle to say “I was wrong” or “I’m sorry” without additions

Common Deflecting Tactics and What They Look Like

Recognising your go-to tactic is the first step towards building alternatives:

| Deflecting Tactic | Example Phrases | Underlying Emotion/Need |

|---|---|---|

| Blame-shifting | “Yes, but you always…” | Fear of being seen as inadequate |

| Subject-changing | “That reminds me, did you…?” | Anxiety about emotional intensity |

| Humour/Sarcasm | “Oh, here we go with the lectures again” | Discomfort with vulnerability |

| Minimising | “You’re overreacting” | Fear of consequences |

| Counter-accusing | “Well, you did the same thing last week” | Need to maintain equality/power |

| Victimhood | “Why is everyone always attacking me?” | Overwhelm and helplessness |

| Intellectualising | “Actually, research shows…” | Avoiding emotional connection |

| Stonewalling | Silence, leaving the room | Complete emotional overwhelm |

When Deflecting Becomes Problematic

Whilst occasional deflecting is human, it becomes concerning when it:

- Prevents resolution of recurring conflicts

- Creates distance in close relationships

- Stops personal growth and learning

- Becomes your automatic response to any feedback

- Leaves others feeling unheard or invalidated

- Interferes with work performance reviews or professional development

How Deflecting Affects Your Relationships and Wellbeing

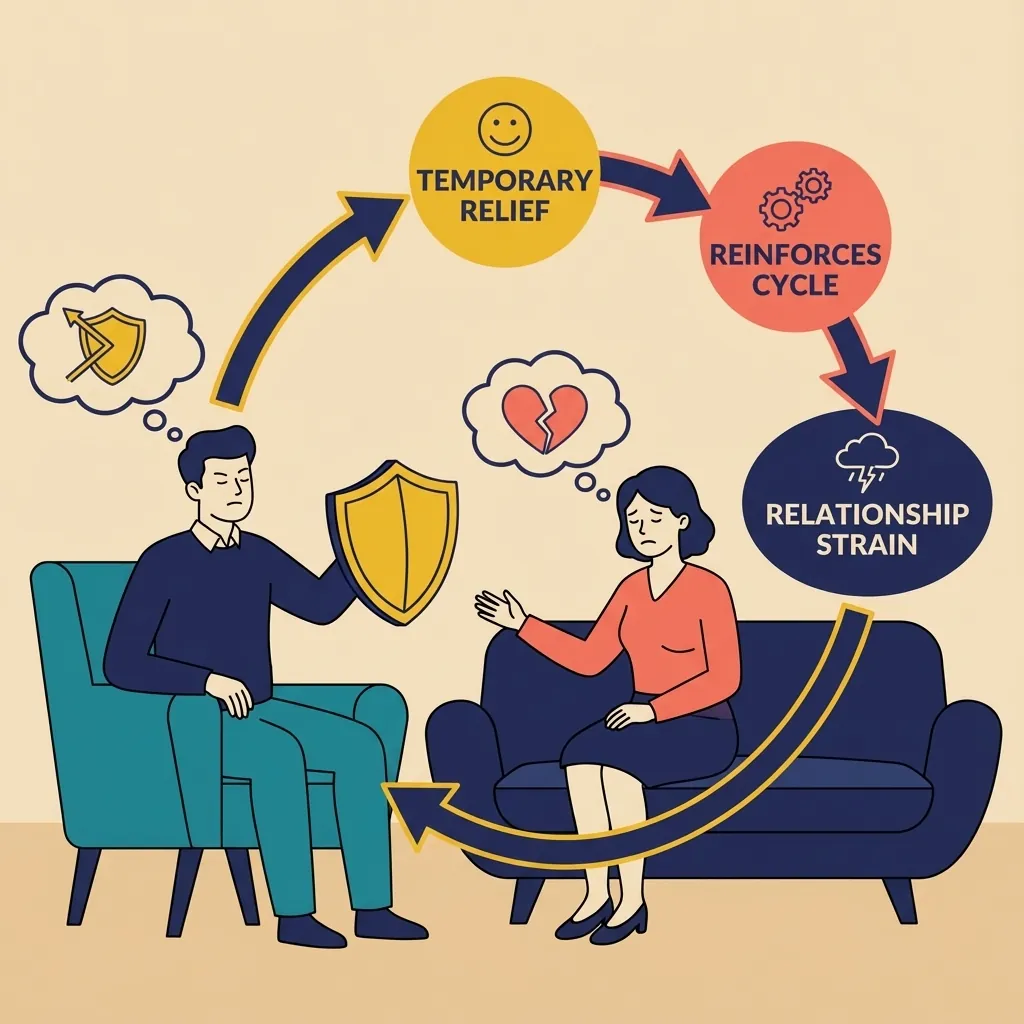

The short-term relief deflecting provides comes at a significant long-term cost. When you understand these effects, you often feel more motivated to do the harder work of changing old patterns.

The Relationship Toll

When we consistently deflect, our partners, friends, and colleagues eventually stop trying to engage meaningfully with us.

Consider a common pattern: one partner deflects whenever concerns arise (“You’re never satisfied” or “We’re fine, you worry too much”). Eventually the other partner stops sharing altogether. Dinner conversations stay surface-level – work logistics, weekend plans. The person you once told everything now gets the headline version.

This pattern – deflection leading to withdrawal leading to disconnection – appears across countless relationships struggling with communication.

Impact on Self-Awareness and Personal Growth

Deflecting doesn’t just push others away; it keeps us strangers to ourselves. When we can’t acknowledge our mistakes or examine our behaviour honestly, we remain stuck in patterns that no longer serve us. The paradox is that deflecting to protect our self-esteem actually undermines it.

The Vicious Cycle of Deflection

Deflecting creates a self-reinforcing pattern: we deflect to avoid discomfort, which prevents us from developing skills to handle discomfort, making us more likely to deflect next time. Meanwhile, relationships deteriorate, confirming our unconscious fear that vulnerability leads to rejection, strengthening our deflection reflex.

If deflecting is affecting your relationships or self-esteem, you don’t have to navigate this alone. Therapy Central’s CBT-trained therapists offer online and London-based support, with flexible scheduling from early morning to late evening, including weekends. Reach out to explore how we can support you.

Evidence-Based Strategies to Stop Deflecting

Breaking deflecting patterns requires patience, practice, and often professional support. These evidence-based techniques from CBT, DBT, and compassion-focused therapy can help you develop healthier responses.

Challenging Cognitive Distortions in Real-Time

When you notice the urge to deflect arising, catch the thought driving it. Ask yourself:

- Reality testing: “Is this feedback genuinely catastrophic, or am I catastrophising?”

- Evidence gathering: “What actual evidence supports or contradicts this criticism?”

- Alternative explanations: “Could their concern come from care rather than attack?”

Write down the deflecting thought and challenge it. Perhaps, “If I admit I forgot that deadline, everyone will think I’m incompetent forever” could become “I made one mistake. My track record shows I’m usually reliable. Admitting this won’t erase my strengths.”

Building Distress Tolerance

Many people deflect because emotional discomfort feels intolerable. Building your ability to experience difficult emotions without immediately escaping them helps you stay present long enough to respond differently. Here are a few steps you could consider taking:

- Week 1: When feeling defensive, commit to listening for 30 seconds before responding. Find your anchor. This might feel difficult – your nervous system is fighting to keep its old protection. Do it anyway.

- Week 2: Extend to one full minute

- Week 3: Listen to the entire concern before formulating your response

- Week 4: Add a reflection statement: “What I’m hearing is…” before sharing your perspective

Grounding with the 5-4-3-2-1 Technique

When defensiveness rises and you feel the deflection urge, ground yourself in the present moment:

- 5 things you can see: Notice details in your environment

- 4 things you can touch: Feel the texture of your chair, your clothing

- 3 things you can hear: Traffic outside, someone’s breath, a clock ticking

- 2 things you can smell: Coffee, fresh air, your own skin

- 1 thing you can taste: Your mouth, a sip of water

This interrupts the amygdala hijack, bringing your prefrontal cortex back online so you can choose your response rather than reacting automatically.

Practising Vulnerable Communication

Replace deflecting responses with vulnerable alternatives:

- Instead of “That’s not true,” try “That’s hard to hear”

- Instead of “You do it too,” try “You’re right, I did do that”

- Instead of changing the subject, try “I need a moment to sit with this”

- Instead of minimising, try “Help me understand why this matters to you”

These phrases feel uncomfortable initially, but that discomfort signals growth, not danger.

Self-Compassion: The Antidote to Defensive Patterns

Self-compassion reduces the need to deflect by making mistakes feel survivable. Try this self-compassion break when you notice deflecting urges:

- Acknowledge the difficulty: “This is a moment of suffering”

- Normalise the experience: “Difficulty is part of being human”

- Offer yourself kindness: “May I be kind to myself in this moment”

Research shows self-compassionate people are actually more likely to take responsibility because admitting mistakes doesn’t threaten their entire self-worth. 5

Creating Accountability Structures

Share your intention to reduce deflecting with trusted friends or your therapist. Ask them to gently point out when you’re deflecting, using an agreed-upon signal or phrase.

Consider keeping a “deflection diary” noting:

- When you deflected

- What triggered it

- How you felt physically and emotionally

- What you feared would happen if you didn’t deflect

- An alternative response you could try next time

When to Seek Professional Help for Deflection Patterns

Whilst self-help strategies are valuable, some deflecting patterns require professional support to address safely and effectively.

Signs It’s Time for Therapy

Consider seeking professional help if:

- Deflecting is damaging important relationships despite your efforts to change

- You experience panic or severe anxiety when trying not to deflect

- Past trauma makes vulnerability feel genuinely unsafe

- Deflecting accompanies other concerning patterns (substance use, self-harm, severe mood changes)

- You can’t identify why you deflect despite sincere self-reflection

- Work performance or career advancement suffers due to inability to accept feedback

How Therapy Addresses Deflecting

At Therapy Central, our approach to deflecting patterns integrates multiple evidence-based frameworks:

CBT helps identify and challenge the thoughts driving deflection, developing practical alternatives to defensive responses. 6 You’ll learn to recognise cognitive distortions in real-time and practise balanced thinking.

Schema therapy explores early experiences that created deflecting patterns, helping you understand and heal the wounded parts that still seek protection through deflection. 7

Mindfulness-based approaches increase awareness of defensive urges before they become actions, expanding the space where choice lives.

Trauma-informed therapy addresses underlying wounds safely, ensuring you develop internal resources before dismantling protective patterns like deflecting.

UK Support Pathways

If you’re in the UK and ready to address deflecting patterns, support is available through several pathways. Your GP can refer you to NHS Talking Therapies for CBT-based support, whilst Relate offers relationship counselling when deflecting affects partnerships. If emotional overwhelm feels unmanageable, the Samaritans (116 123) provide 24/7 support. Therapy Central offers specialised support with flexible scheduling, including evenings and weekends, with both online and London-based options.

Building Authentic Communication Beyond Deflecting

Learning to stop deflecting opens doors to deeper relationships, genuine self-knowledge, and the resilience that comes from facing life honestly. The journey isn’t about becoming perfect at accepting criticism or never feeling defensive again, it’s about developing flexibility in your responses and the courage to stay present even when it’s uncomfortable.

Each time you choose vulnerability over deflection, you’re rewiring neural pathways developed over years or decades. Be patient with yourself. Some days you’ll deflect before catching yourself; other days you’ll catch the urge and choose differently. Both are progress.

The relationships that matter will strengthen as you practise authentic communication. People learn they can trust you with difficult truths, creating space for genuine intimacy. Most importantly, you develop trust in yourself – trust that you can handle discomfort, learn from mistakes, and remain worthy regardless of imperfection.

Ready to break the deflecting cycle? Our qualified and experienced therapists and psychologists provide evidence-based support tailored to your needs. Contact Therapy Central today for a free, no-obligation 15-minute consultation – available online or in London.

FAQ

Is deflecting the same as gaslighting?

No. Deflecting redirects focus to avoid discomfort, often unconsciously. Gaslighting is deliberate manipulation to make someone doubt their reality. Deflecting can occur within gaslighting, but deflecting alone is typically a self-protective reflex rather than intentional psychological abuse.

Can deflecting be a sign of a mental health condition?

Yes, sometimes. Chronic deflecting can signal anxiety, depression, trauma responses (PTSD), or certain personality patterns. It’s often a learnt coping mechanism. If deflecting significantly affects your life, professional support can help identify what’s driving it and offer tailored strategies.

How do I stop deflecting in the moment?

Pause before responding. Notice physical discomfort (tension, defensiveness). Acknowledge the emotion silently: “I feel criticised.” Choose vulnerability: “You’re right, let me think about that” or “I’m finding this hard to hear.” Practise self-compassion; stopping deflecting takes time.

What's the difference between deflecting and setting boundaries?

Boundaries communicate limits respectfully (“I need space to process this”). Deflecting avoids engagement entirely through redirection or blame. Boundaries protect wellbeing whilst maintaining accountability; deflecting shields ego by refusing responsibility. Healthy communication can include boundaries without deflection.

Why do I deflect even when I don't want to?

Deflecting is often automatic, rooted in past experiences where vulnerability felt unsafe (childhood criticism, past relationship trauma). Your nervous system learnt deflecting as protection. Recognising the pattern is the first step; therapy (especially CBT) helps rewire these responses.

Can therapy help with deflecting behaviour?

Absolutely. CBT identifies deflecting triggers and cognitive distortions. Therapists create safe spaces to practise vulnerability, explore underlying fears (rejection, shame), and develop healthier communication skills. Therapy Central’s qualified practitioners offer evidence-based support for changing defensive patterns.